The cultural implications of skin whitening products and their use.

A series of corporate announcements in 2020 signaled what seemed to be an important moment for the cosmetics sector.

This was as Black Lives Matter amplified calls for racial justice across the US.

With multinationals pressured by the public to express support for racial equality, consumers were quick to highlight the inconsistency between companies’ public statements and their continued promotion of creams, serums and lotions promising to “whiten” users’ skin.

In response, several major skincare manufacturers pledged to revise their branding and product lines.

Johnson & Johnson said it will stop selling skin whitening products in Asia and the Middle East.

L’Oreal pledged to eliminate words such as “whitening” or “fair” from their ranges.

So did Unilever, which also bowed to growing pressure by renaming its controversial South Asia-focused brand, Fair & Lovely, to Glow & Lovely.

Beiersdorf AG (Nivea’s parent company) also disassociated itself from terms like “whitening” or “fair,” explaining to Allure magazine it was conducting an “in-depth analysis” of its product offering and marketing strategy.

According to the German company, it said last year that the company had completed the review.

It also took extensive consumer research into consideration and decided not to communicate with customers who do not “reflect the diverse skin tones of our consumers.” “For campaigners, these were small but significant steps toward rewriting industry narratives equating beauty — and, often, success and happiness — with whiteness.

Visit any one of the cosmetic giants’ sites from Europe and America today to see explicit references about skin color.

It’s quite different if you go from Asia, Africa, or the Middle East.

L’Oreal’s Singapore website, for example, still promotes creams and serums that have “powerful whitening” capabilities, while the Indian site stocks a moisturizer called “White Activ”.

The Chinese word for “whitening” is “white”, which literally means “beautiful” in Chinese.

L’Oreal recommends using a mask to whitening your skin.

Recent social media advertisements for mainland China offer a “whitening miracle” or “mild-whitening” that will “blow the spring breeze across your face.

Japan uses the term “bihaku”, which also combines “white” with “beautiful”, to describe its products.

Unilever seemed to have different messages for different groups, even within the same geographic region.

Take one of its most popular skincare brands, Pond’s, whose English US website is free from the word “whitening,” while the Spanish version operated an entire website section openly branded as “whitening” until CNN reached out for comment about the page.

In Thailand, meanwhile, customers can buy a range of products marked “White Beauty” including sunscreen and facial cleanser.

Fair & Lovely is now called Glow & Lovely.

However, Fair & Lovely’s packaging still features lighter skinned South Asian models.

Unilever also continues to sell its “Intense whitening” facial wash in India via the Lakme brand.

Block & White is the Philippines’ conglomerate.

This range, which was marketed as a sunblock but boasted its “intensive whitening”, formula and “5-in-1 Whitening essentials,” has been referred to in the Philippines.

Amina Mire, who is a researcher in the skin whitening field for over 20 years, thinks that multinational companies are not taking meaningful action because of continued marketing of products that claim to lighten skin.

While she recognizes that recent corporate announcements are “100% a step in the right direction,” the sociology professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, thinks that multinationals will “not make any concessions — or at least very little concession — in the Asian market.

They are improving their websites.

.

.

CNN’s Mire said that they knew who their clients were on their billboards, and their marketing.

Mire claims that brands would resist calls to soften messages used to target women outside the West, because consumers in many of those markets “demand” explicit reassurances that the products whiten skin.

In a statement, L’Oreal it has “made updates” to its product ranges, but that “due to manufacturing schedules and also product registration and certification requirements, this transition is not fully complete across all markets and materials.

” A spokesperson added that the company is “committed and focused on removing the term ‘whitening’ as fast as possible in all markets.

” Company spokespersons also stated that “bihaku” and other East Asian words are regulated and used “commonly in these markets to describe a radiant, even and healthy skin tone.

Unilever spokesperson said, “Fair,” “white”, and “light” are no longer used by the company as these terms suggest an ideal beauty we do not believe is correct.

According to the statement, “nearly every” company packaging has been updated.

According to the spokesperson, “Consumers might still find older packaging due to factors like stock pipelines or marketing descriptions from third-party websites.” Some cosmetics companies, unlike Unilever or L’Oreal have tried to keep the topic quiet, avoiding accusations of hypocrisy.

For instance, Japanese cosmetics giant Shiseido, whose high-end skin products are now widely available in Europe and the US, has made no public announcements regarding the branding of its “White Lucent” range.

CNN asked Shiseido about the matter last year.

The company replied that their products did not “have the ability to lighten the skin.” It also stated that it does not recommend or sell any whitening products.

Shiseido declined CNN’s request for further comment on the matter.

Others appear to be making good on their promises.

Online searches conducted by CNN on websites operated by Johnson & Johnson, which dropped its Neutrogena Fine Fairness and Clean & Clear Fairness lines from Asian and Middle Eastern markets in 2020, found no examples of the word “whitening.

” Johnson & Johnson did not respond to CNN’s request for comment.

Nivea’s name which the company claims translates to “snowwhite,” seems to have chosen a different course.

CNN discovered that Nivea, whose name means “snow white” and is almost two years since Beiersdorf AG made promises of changes, had a regional FAQ that acknowledged that beauty in Asia or Africa was often linked to having a lighter skin tone.

Nivea doesn’t promote skin lightening and its products don’t have any effect on skin color.

India-sold products were still advertised as “whitening” (or “extra whitening”) Nivea Malaysian’s website continued to feature a section titled “whitening,” with a light-skinned model to appeal to customers in this southeast Asian nation.

CNN contacted Beiersdorf AG to remove these pages and their products.

Products in Nigeria still provide “natural fairness.” “It isn’t hard to decipher why a gap between words and actions may persist.

According to the company, “Nivea products containing whitening ingredients continue to be our largest sellers in Asia.” “In statement, a spokesperson for Beiersdorf AG said that products using the term “whitening” are “in the process of being changed” and that “adaptations to our product communication will become more visible .

.

.

In the next months, it will be gradually.

The company said it is “on a journey and .

.

.

It is committed to improving its products and services and “typically develops, produces and markets on a local basis to meet consumer demand.” Mire believes terms such as “glowing”, “brightening” and other similar phrases, which are used more frequently by cosmetics manufacturers as substitutes, are just as rooted in colonial or racial narratives than the words that they replace.

Mire believes that these cosmetics continue to use historical and racialized connections between skin color and social status.

Mire stated that although the word “whitening” has “become problematic”, she said that it still links lightness with urban progress and style with sophistication.

.

.

with aspects of globalization and modernity.

L’Oreal’s statement to CNN stated that the term “brightening”, which refers to products that target concerns such as uneven skin tones, blemishes or spots due to UV radiation, was appropriate.

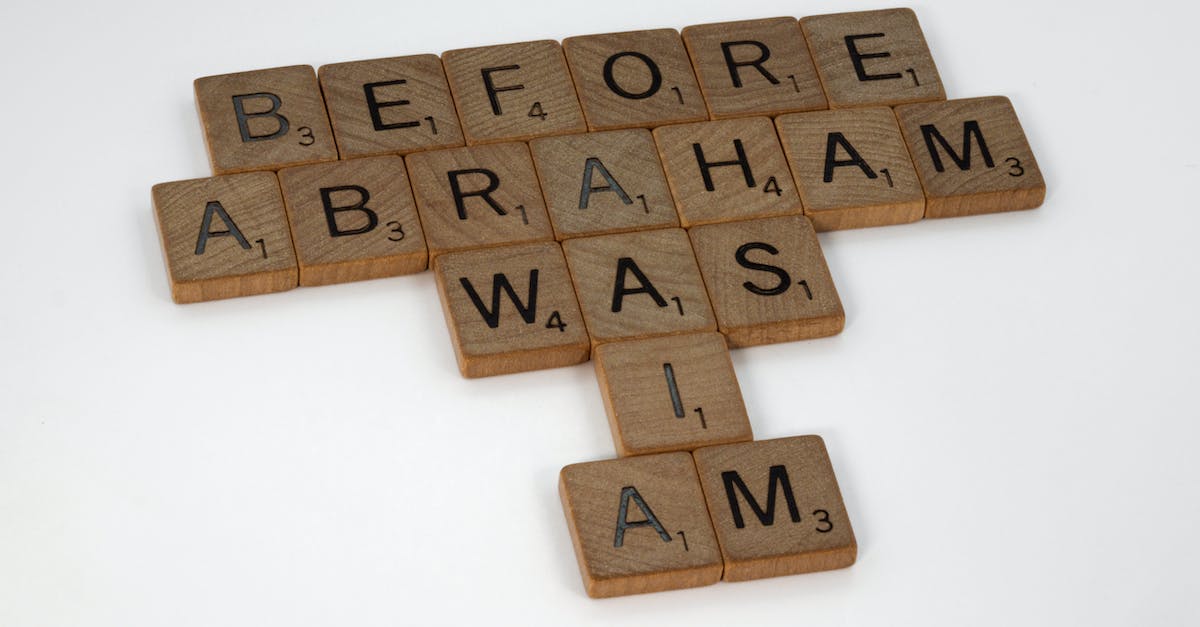

“A troubling contradiction” If the campaign to rename Fair & Lovely was a pivotal moment against skin whitening then Chandana Hiran, an Indian student was one of the key players.

She created the #AllShadesAreLovely petition that attracted over 35,000 signatures.

This brought attention to a brand not well-known beyond Asia and Africa.

For Hiran, who is set to join an MBA program at Canada’s Ivey Business School, the campaign’s apparent success left her with mixed emotions.

Hiran, who is currently in Mumbai to pursue an MBA program at Canada’s Ivey Business School, stated that her initial reaction was “it’s a step forward.” She also said that the campaign was a tacit acknowledgement of “what was wrong in the past.” But, the campaigner of 24 years soon realized that the original name was prominently featured on the products.

This message is sent to customers as “Fair & Lovely” and reads: “This shows that the manufacturers have changed the branding but not distanced themselves from the product itself, Hiran said, adding: “Nowhere in the marketing or advertising do they acknowledge why it became Glow & Lovely or why there was a problem with Fair & Lovely.

Hiran pointed out that Unilever’s use of “whitening”, “fair” and other words in their empires, like the Block & White or Lakme brands, creates a disturbing inconsistency.

Hiran asked, “If they are aware this problem is in one region why don’t they do it in all regions?” Waiting for someone to tell you that it is necessary to make the changes in your area doesn’t seem right.

“Unilever declined to comment on questions relating to Glow & Lovely, including queries on historical advertising campaigns and plans to remove the brand’s old name from its packaging.

The woman trying to end the skin-whitening market.

Assistant professor of strategy and policy at National University of Singapore Business School Arzi Adbi said that he thinks these firms promote beauty ideas that are linked to lighter skin, and that they fuel demand that may indirectly pose a risk to people’s health.

Although multinationals’ skin whitening creams do not typically contain toxic chemicals such as mercury, Adbi’s research suggests that they still help create a market for more potent, cheaper locally made products that often contain harmful ingredients.

“(The multinationals’) corporate governance standards are relatively higher: They do their audits and are careful about not launching a product that will cause physical harm,” he told CNN.

However, once you legitimize a skin whitening market, you cannot control the smaller local companies in India.

.

.

Launch riskier, stronger products that can whiten the skin temporarily but cause long-term side effects.

Adbi described Unilever’s decision not to use the term “fair” in its brand as “extremely cosmetic.” He said it was a better move to acknowledge the influence of past advertising campaigns which suggested lighter skin could lead to improved outcomes.

Abdi stated that if they really meant it they would apologize for their Indian TV ads.

These commercials showed women with darker skin not being able to get good jobs and husbands until they started using these products.

Similar promotional campaigns have been condemned by many other brands.

In 2008, a controversial Pond’s ad series saw Bollywood star Priyanka Chopra play a character who wins back her lover by using the products to get a “pinkish-white glow” (she apologized for her role in the commercials in her 2021 memoir).

In 2017, Dove apologized after posting a social media ad showing a Black woman removing her brown shirt to reveal a White woman in a lighter-colored shirt underneath.

Nivea’s billboards advertising “visibly fairer skin” in Ghana, West African countries and elsewhere were also criticised.

NPR was given a statement by Nivea at that time.

It stated its campaign was not meant to denigrate or glorify anyone’s skin care needs.

The company also said the products were designed to protect the skin against long-term skin damage and premature skin ageing.

“Hiran echoed Adbi’s call for beauty companies to actively acknowledge and renounce problematic past campaigns, remembering the impact they had on her as a child growing up in India.

“I would feel insignificant,” she stated.

She said that she felt like nobody was going to marry her and that all the advertisements for fairness cream were true.

You would not find a partner, you would not be selected for a job, you will be discriminated against, bullied.

For a very long time, my self-esteem was low.

“That story was held by the whole society,” she said.

Everyone was involved.

“Today, the narrative is, slowly, changing.

The messages that you hear, and how loudly they are heard, will depend upon where you live..

Adapted from CNN News